Why Use RDF

Copyright 2025 Kurt Cagle / The Ontologist

Here’s a question? Is this RDF?

Example #1

@prefix ex: <http://www.example.com#> .

@prefix rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#> .

@prefix schema: <http://www.schema.org/> .

@prefix : <http://www.schema.org> .

ex:JaneDoe a :Person ;

:name "Jane Doe"^^xsd:string ;

:jobTitle "Professor"^^xsd:string ;

:telephone "(425) 123-4566"^^xsd:string ;

:url <http://www.janedoe.com> ;

:employer ex:BigCo ;

.What about this?

Example #2

<Person rdf:about="ex:JaneDoe"

xmlns:ex="http://www.example.com#"

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns="http://www.schema.org/">

<name>Jane Doe</name>

<jobTitle>Professor</jobTitle>

<telephone>(425) 123-4567</telephone>

<url>http://www.janedoe.com</url>

<employer rdf:resource="ex:BigCo"/>

</Person>Oh, hey, and this?

Example #3

{

"@context": {

"@vocab":"http://schema.org/",

"ex":"http://www.example.com#"

},

"@graph":[

{"@id":"ex:JaneDoe",

"@type": "Person",

"name": "Jane Doe",

"jobTitle": "Professor",

"telephone": "(425) 123-4567",

"url": "http://www.janedoe.com",

"employer":{"@id":"ex:BigCo"}

}]}Maybe this?

Example #4

id,type,name,jobTitle,telephone,url

ex:JaneDoe,Person,"Jane Doe","Professor",_

"(425) 123-4567","http://www.janedom.com"

---

prefix,namespace

default,"http://schema.org/"

ex,"http://www.example.com#"

schema,"http://schema.org/"This, perhaps?

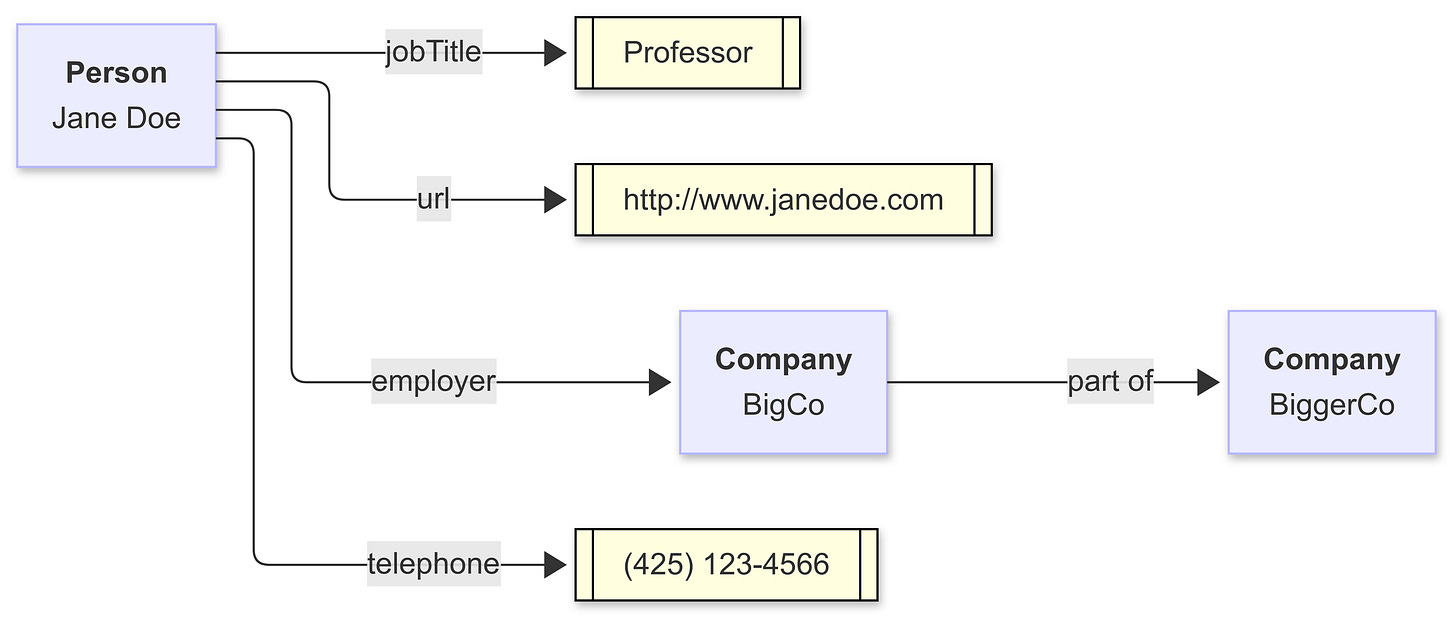

assuming that the diagram is generated as follows:

Example #5

flowchart LR

%%prefix schema: <http://schema.org/>.

%%prefix ex: <http://www.example.com#>.

%%prefix : <http://schema.org/>.

ex:janeDoe[<b>Person</b><br>Jane Doe]

ex:BigCo[<b>Company</b><br>BigCo]

ex:janeDoe --> |jobTitle| literal1[["Professor"]]:::literal

ex:janeDoe --> |telephone| literal2[["(425) 123-4566"]]:::literal

ex:janeDoe --> |url| literal3[[http:\/\/www\.janedoe\.com]]:::literal

ex:janeDoe --> |employer| ex:BigCo

classDef literal fill:lightYellow,stroke:black;The answer in all cases is “yes”. These are all RDF.

How can all of these be RDF? There is a pervasive misconception about RDF, namely that it is a format. After all, Turtle (example 1) is a format, as is XML (example 2), JSON (example 3), CSV (example 4), and even the diagram language Mermaid (example 5). They are ways of representing data, but significantly, these are all ways of representing the same data.

The Evolution of Data Representations

Data representation has evolved. The oldest computer data formats were fixed-width field formats because they worked best with Hollerith punch cards. In this particular case, there were usually two pieces to fixed-width formats: A schema, which indicated how large and in what order each field was listed, as well as a basic indication of “type” (string, integer, date, etc.), and a data row, which followed this schema.

SQL was originally a fixed-width format for precisely that reason. Each record essentially represented a Hollerith card, even when the card itself was no longer physically present. It also emerged at a time when modems and ethernet connections were just beginning to standardize (in the late 1970s and early 80s), where transmission speeds were very, very … very slow, so you needed to optimize the “packet size” of the record when sending it over the wire.

The need to specify the exact number of characters decreased as both computing power and bandwidth increased. Instead, systems began using column names, a form of tagging, to transmit information, with each column name then carrying a certain limited semantic information. The use of field delimited values (such as the comma-separated value (CSV) or tab-separated value (TSV) format emerged about the same time as spreadsheets in the mid-1980s.

Publishers also frequently needed to embed information into small mnemonics to pack as much as possible into each message. As text content became more prevalent (especially in areas such as typesetting), typographers would embed such mnemonics into their code to indicate changes in presentation (make this section bold, use that font for this line of code, insert a page break, and so forth). The individual mnemonics became known as tags, and tagging (or markup, from the practice of marking up a manuscript with a pen or marker) became a big business, as it made it possible to capture not just simple text but presentation and meaning as well within a document.

HTML caught the world by storm in the mid-1990s with a simple-to-use document object model and an intuitive markup language for building that model. By the mid-1990s, developers working with the new medium began constructing arbitrary data tags, and the idea of encoding data with such tags took off with the publication of XML (the Extensible Markup Language) in 1998. Unlike CSV, a very flat document model, XML was much richer, especially with its ability to separate schema from document/data. It became the default for working with data for nearly a decade.

In 2007, Douglas Crockford, then at Yahoo, made the case that, for web developers, XML was too heavyweight, and worse, that it didn’t fit into the paradigm that Javascript developers in particular used, a model built around the Javascript objects and arrays, so he developed a format that more closely aligned with those requirements, called the Javascript Object Notation or JSON. For a while, JSON eclipsed XML in the data representation space, although XML remains strong in document representation.

Other formats, such as the Yet Another Markup Language (YAML) got their start in configuration files, though it is also increasingly being used for data representation. It makes use of indented tagged content. Similarly, Markdown has, in recent years, gained more of a hold as a condensed page representation similar to HTML but using many symbolic shortcuts.

One of the more significant problems with this proliferation is that data format representations don’t carry much semantic information. JSON, in particular, is not particularly well suited for large-scale data integration, partially because it has no consistent mechanism for indicating links and in part because, even today, JSON tends to be underspecified in terms of structural representation. This makes it okay if you have control over both the client and the server. Still, as multi-node service architectures (data meshes and AI nodes) become more pervasive, the shortcomings of JSON, in particular, are making it difficult to adapt.

Understanding RDF

In 2004, Tim Berners-Lee, James Hendler, and Ora Lassila published an article in Scientific American that laid out a new concept they had been developing for the previous four years - the Resource Description Framework, or RDF, as a way of creating a generalized, abstract, distributed database. The paper was warmly received, but the timing - coming as it did during the depths of the dot-com crash - and the somewhat abstruse nature of the paper meant that other developments eventually eclipsed it.

Part of this eclipse also had to do with the fact that while RDF was brilliant, it was too early. Companies were just beginning to hook up data to web servers. The concept of REST (REpresentational State Transfer), which underlies a lot of the architectural underpinnings of RDF, had only been formulated a few years before, and most of the active development of RDF was taking place primarily at the academic level.

I came to RDF in 2003, primarily because I had been working on a book about XML, REST, and XQuery, and much of what I was seeing with regard to XQuery turned out to be very applicable to RDF as well. Most of it came down to how to create a database without an actual database program. The solution comes down to the notion that you must create universally unique keys.

As it turned out, the way that web addresses - Uniform Resource Locators or URLs - were minted generated a pretty good approximation of a globally unique string. Uniform Resource Identifiers (URIs) consequently can be just a numeric key such as a UUID, but URIs also have just enough semantics to be understandable. This became very important for property relationships, especially, as performing logical retrieval of information was very dependent on making sure that you knew which properties were being used.

RDF is predicated on a few primary concepts:

All data representations can be reduced to graphs.

Each node in that graph represents a concept or entity.

Each edge in that graph represents a relationship.

each node and edge has one or more specific global addresses or identifiers (called IRIs).

The sequence of node-edge-node is called an assertion (also known as a triple or n-tuple). These are designated as the subject, predicate, and object of the triple, respectively.

An object (the third part of the triple, can either be an identifier to another node, or a given as a combination of a string and some kind of a data type. From the standpoint of RDF, these are mostly the same things.

A graph consists of a collection of triples, usually where the object of one triple may be the subject of another.

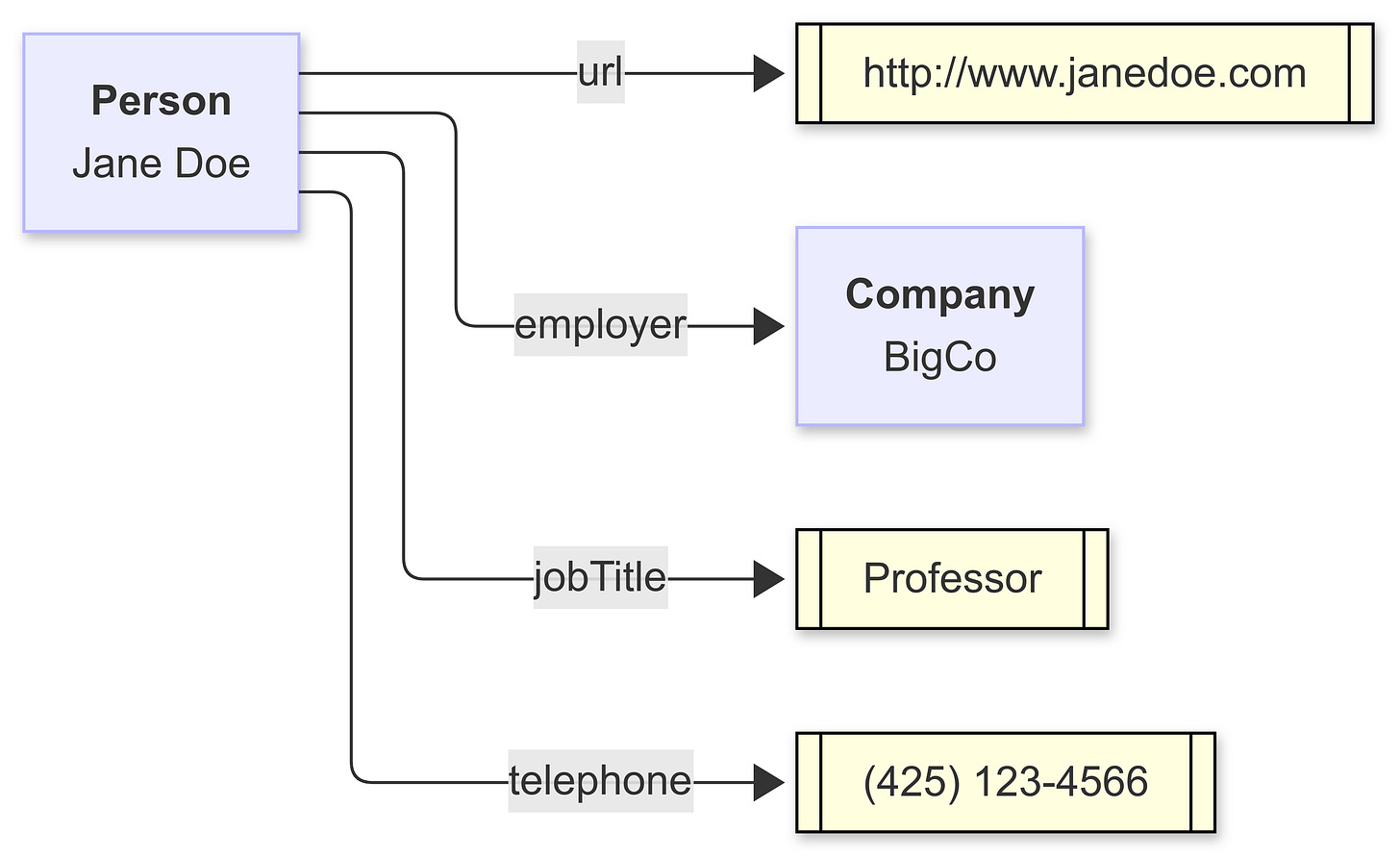

All that sounds complicated, so let’s go back to the picture I posted earlier:

This is a graph. One statement of that graph is that a person has an employer (specifically, Jane Doe has the employer BigCo, a very big, very important company, trust me on this). Jane Doe is the subject, BigCo is the object, and “employer” is the predicate or relationship. BigCo may very well have either in-bound or out-bound arrows attached to it.

Another relationship that Jane Doe has jobTitle, though in this case, this is a literal value (in other words, a string or sequence of characters). The data type of that literal is, in fact, String in the traditional sense. The telephone for Jane Doe is also a string, but it’s one that has a well-specified structure or pattern. We could say that the telephone literal is a string with a qualifying pattern, such as “^\(\d{3}\)\s*\d{3}\-\d{4}$”, which is a regular expression that says a phone number is a sequence of text that has three numbers within a set of parenthesis, followed by a space, followed by three more numbers, followed by a dash, followed by four more numbers. By specifying a pattern or other restrictions on a string, you can “subclass” the resulting object and can name it something like the “Phone Number” datatype.

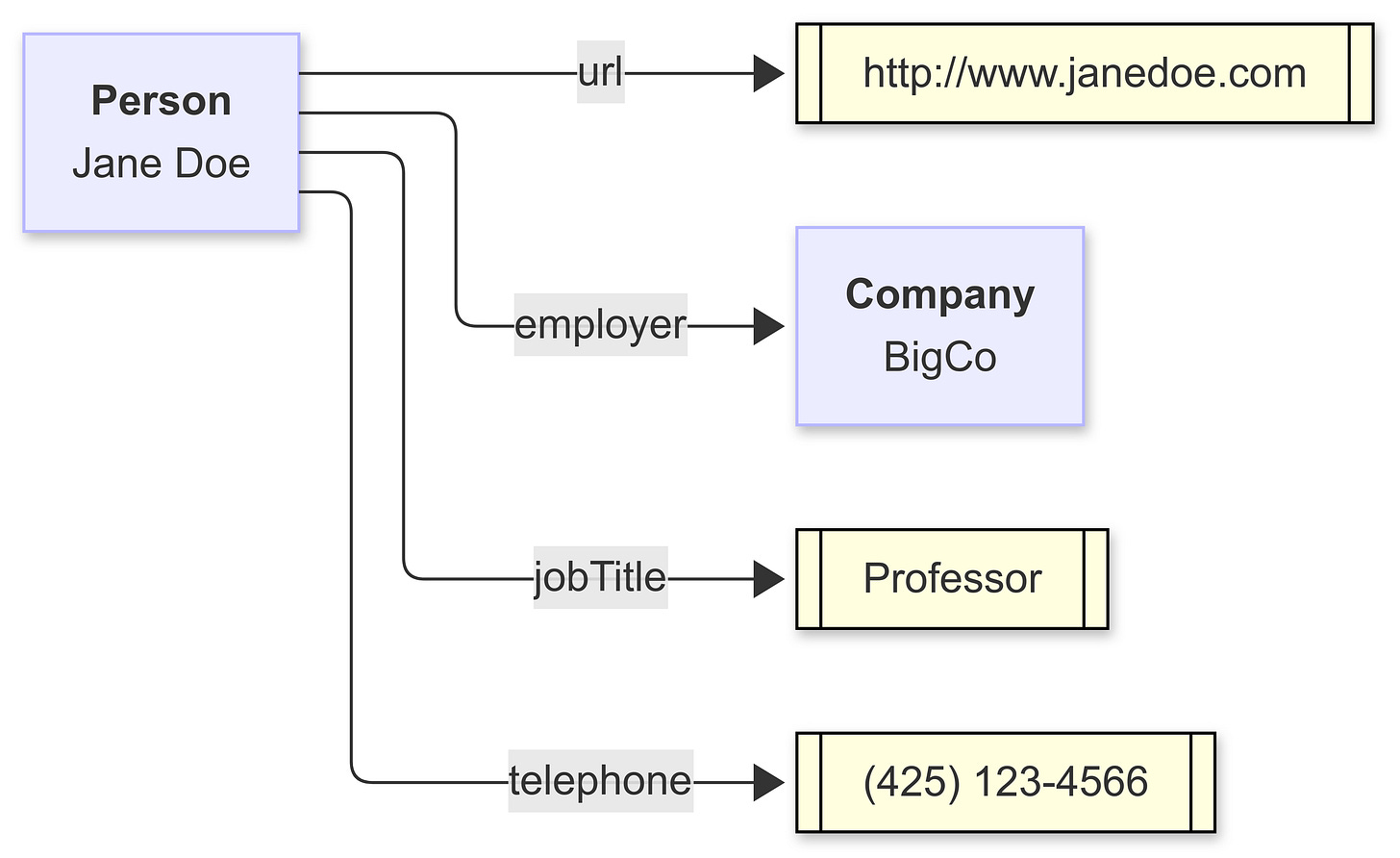

Literals (usually) do not appear as subjects. Extending the diagram out a little bit, you can see a somewhat more typical-looking graph:

Each of the blue boxes has some kind of identifier, such as ex:JaneDoe, where ex: is a shorthand term (a prefix) for a long unique string (here, http://www.example.com#JaneDoe) called an International Resource Identifier (IRI). In a relational database, identifiers are local to their tables, and it is the role of the database to connect (also known as join) one identifier in one table with the same identifier in another. In a graph, the mechanism to do the lookup is abstract.

This means I can talk about something (like a person or organization) simply by referencing its identifier — even if that identifier is in a different database on the other side of the planet. It also means that if you say something about Jane Doe through her identifier, and I say something about Jane Doe through the same identifier, we’re talking about the same person (technically conceptual person here, as Jane Doe is, in reality, a fictitious entity representing an unidentified person. However, I’d rather not get into that can of worms.

The Power of Context

It is worth taking a diversion into the topic of namespaces, prefixes and context. JSON seems like a simple solution. Why can’t I say - I will call a particular property “jobTitle” and be done with it? We all know what job title means, right? Well, not really. A job title can be a position a given person holds in an organization. It can also indicate a particular run of a specific batch in batch processing. It can be the position that the Biblical character Job had. Yes, this last is a bit of a stretch, but the point is that properties, in particular, are ambiguous without context.

What is context? That’s a profound question. Context is information that makes a specific particular statement make sense. If I make the statement “I have a cat”, then context includes both who that certain “I” is and what exactly a “cat” is, not to mention what we mean by “have”. Describing all that every time we make a statement can get tedious, especially when dealing with a language that may have tens or hundreds of thousands of terms and concepts.

A namespace is a way to identify that context, to say, “if you really need to get a better understanding, here’s a dictionary, several PDFs, and sixteen Youtube videos to help you understand my particular frame of reference. For now, we can agree that these words are defined in this context and we can move on to discussing important stuff, like what do I feed the particular beast.”

The problem with namespaces is that they are long and awkward and difficult to read or repeatedly type. This is necessary to ensure uniqueness, but it’s still a pain in the butt. This is why, in the privacy of your home, you can give the namespace a temporary name, such as ex: for the namespace “http://www.example.com#”, or schema: for the namespace “http://schema.org/”. In XML, JSON, or other formats, the expression schema:jobTitle is a condensed form of the URI “http://schema.org/jobTitle”. These temporary names for namespaces are called prefixes, and the combination of a prefix and a local name such as jobTitle, is collectively called a condensed URI or curie.

A second use of context is also emerging, primarily with JSON-LD (short for JSON-Linked Data, another form for RDF). In this particular case, the context is the association of given namespaces to prefixes, as well as the association of URIs in general to temporary names.

You can see this in Example #3 from above, an example of (one profile of) JSON-LD.

{

"@context": {

"schema":"http://schema.org/",

"ex":"http://www.example.com#",

"@vocab":"http://schema.org/",

},

"@graph":[

{"@id":"ex:JaneDoe",

"@type": "Person",

"name": "Jane Doe",

"jobTitle": "Professor",

"telephone": "(425) 123-4567",

"url": "http://www.janedoe.com",

"employer":{"@id":"ex:BigCo"}

}]}The context is identified by the “@context” tag and contains three namespaces prefixes - one for schema.org, one for example.com (which is a catch-all used primarily to illustrate namespaces as a pedagogical device) and one “special” namespace called “@vocab”. This last one is the default namespace used in the associated graph, meaning that if a tag doesn’t have an associated namespace, then use the default namespace. Here, that default namespace is the same as schema.org; without the default, the same JSON-LD looks like the following:

{

"@context": {

"schema":"http://schema.org/",

"ex":"http://www.example.com#",

},

"@graph":[

{"@id":"ex:JaneDoe",

"@type": "Person",

"schema:name": "Jane Doe",

"schema:jobTitle": "Professor",

"schema:telephone": "(425) 123-4567",

"schema:url": "http://www.janedoe.com",

"schema:employer":{"@id":"ex:BigCo"}

}]}If you don’t include the context at all, this gets even more unwieldy:

{

"@graph":[

{"@id":"http://www.example.com#JaneDoe",

"@type": "http://schema.org/Person",

"http://schema.org/name": "Jane Doe",

"http://schema.org/jobTitle": "Professor",

"http://schema.org/telephone": "(425) 123-4567",

"http://schema.org/url": "http://www.janedoe.com",

"http://schema.org/employer":{"@id":"ex:http://www.example.com#BigCo"} }]}Thus, the context file serves two purposes - it allows people who agree upon a given namespace protocol to communicate just by sharing the “context file” and saves a lot of wear and tear on your fingers.

You can see this same context at work in other representations. For instance, Turtle (which began to crystalize in 2007 but was not fully standardised until 2013 with the adoption of SPARQL), has it’s version of a context:

# Context

@prefix ex: <http://www.example.com#> .

@prefix rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#> .

@prefix schema: <http://www.schema.org/> .

@prefix : <http://www.schema.org> .

# Graph

ex:JaneDoe a :Person ;

:name "Jane Doe"^^xsd:string ;

:jobTitle "Professor"^^xsd:string ;

:telephone "(425) 123-4566"^^xsd:string ;

:url <http://www.janedoe.com> ;

:employer ex:BigCo ;

.RDF-XML has a context declaration at the root container for a dataset:

<Person rdf:about="ex:JaneDoe"

xmlns:ex="http://www.example.com#"

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns="http://www.schema.org/">

<name>Jane Doe</name>

<jobTitle>Professor</jobTitle>

<telephone>(425) 123-4567</telephone>

<url>http://www.janedoe.com</url>

<employer rdf:resource="ex:BigCo"/>

</Person>Note that the above is not QUITE correct. RDF-XML was one of the oldest RDF representations. As such, it made several assumptions that haven’t necessarily aged well, including that you can’t technically use curies in rdf: attributes. There is currently some effort within the RDF community to make contexts more uniform across RDF implementations.

Why This Matters

There are three distinct technologies right now that are all emerging at the same time - the use of large language models to process and communicate information, the rise of knowledge graphs as ways of storing organizational and enterprise data, and the increasing importance of agentic systems, where you generally do not have control over contexts.

Web developers did not like namespaces. It can be argued that part of the reason for the success of JSON was that web developers don’t like namespaces; they work on the assumption that they control the context space. Yet once you move away from simple point-to-point communication between a client and a single node server, namespaces seem to creep back in because you need some way to create agreement about the terminology's semantics, not just the syntax. This is especially important for machine-to-machine communication in a distributed data system, which is where we are ultimately heading.

JSON-LD with context looks a great deal like JSON without context, but it’s more intelligent - it doesn’t necessarily bring the context with it (that’s a costly proposition), but it does tell you what context someone else is using when you have to process that JSON. JSON-LD is JSON, it’s just JSON that follows a few additional conventions. By following those, JSON-LD becomes context-aware.

What’s more, JSON-LD is RDF. If I have a graph expressed in JSON-LD, then I can express that same graph in XML, in Turtle, and in YAML. I can add the metadata to diagrams and illustrations, adding callouts contextually. If I have a JSON-LD file, then I can make consistent references to known taxonomies without necessarily having to import those taxonomies (which are themselves in RDF). This means that when you and I talk about Jane Doe as a concept, we both can agree we’re talking about the same thing rather than simply assuming that the other person understands you.

One major revolution in the last four or five years has been the rise of language models (LMs). Such LMs are not truly databases - they are more like people make assumptions based upon non-shared context - they may be right. Still, they may also be hideously wrong, and this is one of the reasons that hallucinations occur (I have a long article covering this very topic in the works).

On the other hand, if you can embed IRIs into clusters within an LM latent space, then this not only ensures that when you talk about a context, it’s consistent, but it also means that you can pull in a lot of additional contextual information with a simple identifier, which goes a long way in making LMs more database like even if they will never wholly be such.

RDF takes more effort to encode. There comes a point where you cannot rely solely upon statistical inferencing but need the help of domain experts to classify and curate content, but the payoffs are well worth it. Such data makes reasoning easier and more consistent, reduces erroneous and unclean data, and makes data governance easier to manage. Yet even given that, something as simple as adding a context and namespacing your terms can go a LONG way towards making your data systems more integrated, with remarkably little needed in the way of investment.

In Media Res,

Check out my LinkedIn newsletter, The Cagle Report.

If you want to shoot the breeze or have a cup of virtual coffee, I have a Calendly account at https://calendly.com/theCagleReport. I am available for consulting and full-time work as an ontologist, AI/Knowledge Graph guru, and coffee maker.

I've created a Ko-fi account for voluntary contributions, either one-time or ongoing, or you can subscribe directly to The Ontologist. If you find value in my articles, technical pieces, or general thoughts about work in the 21st century, please contribute something to keep me afloat so I can continue writing.

Creating a Simple Knowledge Graph (and a Pizza) with AI

Building a knowledge graph from scratch can seem like a daunting proposition, but if done right, you can put a pretty decent working ontology together in under an hour with an AI. It should be refined and tested before you put it into implementation, of course, but a big part of building knowledge graphs really come down to doing some homework before y…