Why It's Time To Rethink Linked Data

Or How To Piss Off an Ontologist or Three

In or around 2001, Tim Berners-Lee came up with a very intriguing idea. If you can express information in a graph and give it structure, you can link that structure together with hyperlinks referencing other graph structures, creating a network called Linked Data.

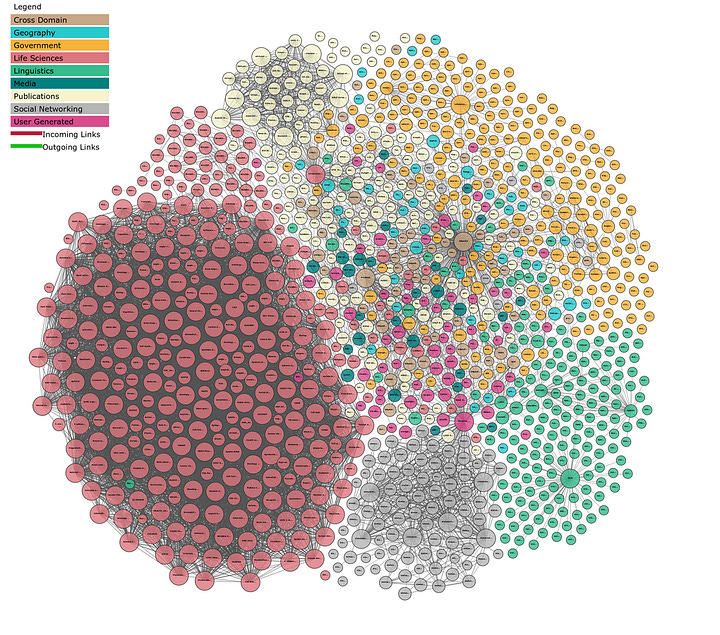

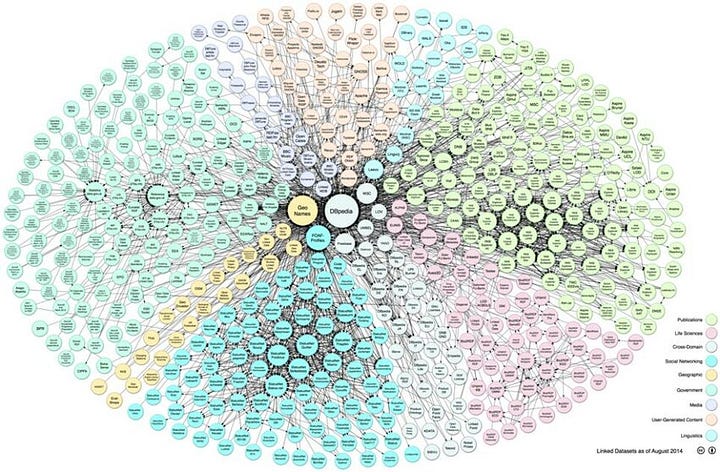

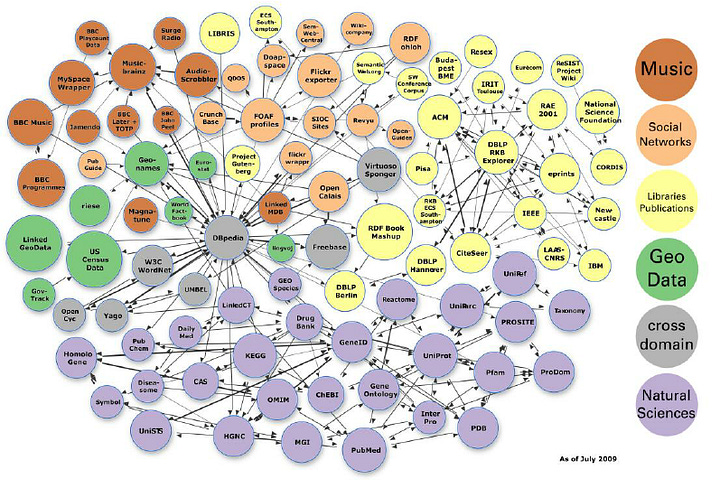

Most people have seen some representation of a Linked Data cloud. For instance:

Each particular node in these graphs is not a single concept but an entire data graph. This looks damned impressive, like some kind of galaxy of stars (or maybe a cluster of galaxies - these things generally fold into hierarchies).

Yet this view of linked data is very misleading for several reasons:

There are a comparatively tiny number of knowledge graphs that are very heavily referenced directly, and a vastly larger number of knowledge graphs that are not accessible at all (in other words, you have a long-tail distribution).

Many knowledge graphs were once accessible, but due to performance or cost issues, they were either shut down or severely restricted in access.

Many knowledge graphs were originally designed assuming static principles, and consequently, they quickly became obsolete.

Similarly, one of the core aspect of knowledge graphs - a working ontology - were not actually included or was very primitive, meaning that there was very little in the way of structure for querying such datagraphs beyond trial and error.

Because of that, this first example of a distributed knowledge system was an interesting failure - interesting because it represented a significant shift in how we think about data, but a failure in that the Linked Data web exists more in potentia than in actuality, even twenty-five years later.

There are several “best practices” that have been passed down from ontologist to ontologist as if they were sacred knowledge. Some of these made sense in the early days of the semantic web, some of them were artefacts of early tools, and some were just design methodologies that were never really challenged, and consequently became perceived wisdom. I would argue that not a few of them are shibboleths, especially as there’s a shift in the industry from OWL to SHACL/SPARQL:

Shibboleth. A custom, principle, or belief distinguishing a particular class or group of people, especially a long-standing one regarded as outmoded or no longer important.

These shibboleths (questionable beliefs) can be outlined as follows:

Adapting Is Better Than Building. It is generally better to utilise existing ontologies rather than creating your own.

Every Ontology Is Global. You must design an ontology with the assumption that the whole world will be using it.

Every Ontology Must Be Inferential. If you’re not using inferencing, why use the semantic web?

Reification Is Bad. Reification is difficult to implement and inefficient, and better models would solve the problem.

Named Graphs Are Bad. Named graphs add to the complexity of systems, with comparatively little benefit, and aren’t compatible with OWL.

Only Ontologists Can Create Ontologies. Data modelling is hard. Let an expert do it.

Let me dig into each of these in further depth.

Adapting Is Better Than Building

The crux of this shibboleth is that it is preferable not to reinvent the wheel. Many ontologies have been created that solve a lot of the modelling issues involved with creating a good data model, and by adapting, you bypass a lot of the design issue and can up and running much faster.

There are two problems with this particular best practice. The first is that design accounts for at most a few weeks or months of work, while maintenance can last years. If an external ontology or data model changes, or if you run into a case where the external ontology no longer meets your particular needs, then you either have to rebuild that particular set of elements in your data model or you have to contort your model into increasingly incompatible ways. I’ve also seen too many situations where an ontology is no longer maintained or has fundamental problems, and this can involve redoing it anyway.

A second problem is more subtle. OWL in particular can be expressed in a number of different ways, and this, in turn, translates into query problems that can often reduce the efficacy of the schema because it requires more specialised SPARQL or similar knowledge for every different component being imported. An organisation that establishes a consistent pattern for designing its schemas will have far more success than organisations that try to cobble together their schemas from different contributors, each of which uses different design patterns.

As an alternative, it is better to use masking or indirection that allows you to identify equivalent nodes between distinct ontologies. This works very well for literal nodes, but in general, for structural object nodes, by creating nodes in your ontology that can then refer to external ontologies, you can add metadata into these definitions that indicate HOW such transformations take place. This is one of the reasons that I like SHACL in that respect - the core ontology is very basic, but it can then be used to identify mappings that are not necessarily one-to-one.

Another way of thinking about this is to think not of utilising external ontologies, but instead to put the onus on building transformations (via CONSTRUCT statements in SPARQL or INSERT statements in SPARQL UPDATES) that will allow you to effectively map from one ontology to another, in a consistent and well-documented manner.

Every Ontology Is Global

An ontology is a way of defining a data model. Some data models are very broad, but they are also rather deliberately limited. Other data models are much more restricted in terms of range and scope - they may be used to create an internal company-wide data model, but with the recognition that such a model will likely not translate well to other businesses that may be in the same topical space.

Scope vs. precision becomes a common duality. The broader the scope, the less precise the model, and vice versa. Moreover, the broader the scope, the more use cases that you need to think about, and consequently, the more complex the ontology becomes. Organisational scopes are useful because you, as an ontologist or data governor, can impose specific modelling methodologies that identify not only what classes and properties are contained, but also what information needs to be contained within these ontologies to be consistent for query purposes.

There is a strong temptation that many ontologists face to want to create THE ONTOLOGY, the One Ring to unite them all. Every so often, that happens, primarily because there is already an established methodology for designing ontologies, but when there isn’t, or when you don’t need to build industry-wide or global ontologies, you’re often better off reducing the scope while being more explicit about how you express everything from labels to data structures to ordering mechanisms. Again, if you want to have something that more or less conforms to an industry standard, identify that standard as a transformation target or source. This is again an operation that generally needs to be performed a small number of times, while the maintenance costs of trying to coordinate industry-wide schemas means that you significantly slow the utility of YOUR data model.

Every Ontology Must Be Inferential

OWL predates SPARQL by approximately seven years, Turtle by about nine years, and SHACL by nearly seventeen years. When OWL first debuted, there were set hard-coded inference rules that made it possible to deal with chaining, transitive closures, linked lists, and so forth. These rules generated in-memory triples that simplified certain operations, but that blew up in the case of others (owl:sameAs It is notoriously known for this, for instance, because it required the near duplication of one set of triples with another, with the object as subject. Other uses of OWL were again tied to interpretations that often were not visible to the user, making them effectively “magical” transformations.

SPARQL greatly reduced the need for inferencing, as you could put a lot of the (business) logic into the query rather than into the data model. SPARQL makes it possible to establish a context of operation in ways that inferencing does not, and without the need for inferencing, much of the heavier requirements that made OWL necessary early are no longer necessary. SHACL provides a way of handling a lot of the core functionality associated with data modelling (cardinality, identification of range and domain, kinds of node and so forth), and SHACL+SPARQL gives you the ability to handle validation in all cases (assuming recursive SHACL structures, which are still in development).

Consequently, inferencing should be seen mainly as an historical artifact, but is becoming more and more irrelevant.

Reification Is Bad

Reification is the process of referring to a particular assertion (subject | predicate | object) with an IRI. In theory, there is no real problem with doing this. Still, in practice, this gets to be complicated because you both have to store that particular association in a triple store in a separate index, and you end up with multiple different identifiers (called reifiers) that can apply to the same assertion. This was actually a part of the initial specification. Many early implementations struggled with this historically, because it meant that every triple actually needed to be described by three triples.

OWL for the most part ignored reification as being unimplementable, even though it was a part of the original RDF specification. The thinking basically went: you can create data models that do what a reifier does readily enough and with greater specificity, so reifiers are primarily syntactic sugar. For a while, this became the established wisdom, and then Neo4J showed up (in 2007). Neo4J became the poster child for Labelled Property Graphs (LPGs), though there are actually very few LPGs with any real traction that don’t generally subscribe to the Neo4J model.

Neo4J makes it possible to place (literal) properties that describe a relationship between two explicit nodes. For instance, if you have two airports, you can create a link called “connects to” that allows you to identify things like a route number, distance between the two airports, air time, and other reference information. In RDF, you could model this as a Connection object, but notationally, that’s cumbersome and awkward without also having some way to deal with multiple different annotations on the same “connects to” triple.

This meant that there were Neo4J statements that were cumbersome to model in RDF. Finally, in 2017, a working group was convened to explore this problem, with the solution emerging several years later as the RDF-Star specification. This of course postdates OWL by two decades, so a lot of the older established wisdom about reifications is not even remotely addressed. RDF-Star is in fact now a superclass of LPGs - you can specify relationships more succinctly with RDF-Star than you can with Neo4J, and you can specify objects as well as literals using the notation, something that Neo4J can’t (yet).

There are still design methodology considerations to come from this, but the established wisdom that reifications are bad design is something that is undergoing re-evaluation.

Named Graphs Are Bad

If reifications are identifiers placed upon triples, named graphs are identifiers placed upon graphs. Again there’s a fundamental tension between those who practiced the semantic web in the OWL era, and those who practiced it during the SPARQL era (roughly 2007-2018), especially post 2013 with the SPARQL 1.1 specification and the introduction of named graphs.

Conceptually, a named graph can be thought of as a label or identifier of a set of triples that collectively define one or more resources. At the time the standard was first proposed, there was a fair amount of opposition to named graphs, primarily because it would require rethinking significant parts of OWL upon which so much of the Linked Data architecture was written. Indeed, it can be argued that SHEX (which would become SHACL) emerged in great part because of the impact of named graphs on OWL and the need to rethink a lot of fundamental assumptions.

Named graphs are especially useful for partitioning information, and (depending upon whether named graphs are visible to hidden to SPARQL) can effectively create envelopes of concern that make it possible to work with specialized subgraphs in isolation from the main (default) graph. There’s a lot of very interesting work being done in this space at the moment, but again most of this post-dates the linked data concept by a couple of decades, and as a consequence, the methodological approach to named graphs is still evolving.

Only Ontologists Can Create Ontologies

A great deal of linked data methodology derived from the first-order logical system work that Douglas Lenat laid out with his work on CYC and Cycorp in the 1990s, and that was then codified conceptually by Tim Berners-Lee, James Hendler, and Ora Lassila produced in the eary 2000s as the Semantic Web. Much of this work in turn traces its origins back to works done in the late 19th century in the Principia Mathematica by philosophers Bertrand Russell and Alfred North-Whitehead.

The term ontology in the modern sense dates back to 1993 in an article by Tom Gruber, who was the first to describe an ontology as “an explicit specification of a conceptualization”. An ontologist, by extension, is someone who could create a specification of a conceptualization, using first-order logic and (implicitly) OWL, with the associated argument that to be able to build ontologies, you needed to be a mathematician with significant experience in first-order logical systems, graph theory, and a deep computer science backgrouns.

However, creating a data model is something that almost anyone can do. For instance, a child would describe a cat as an animal with four legs, fur, a long tail, and makes the sound “meow”. That is a class description for a cat, and any given cat (for the most part) will satisfy those particular constraints. Is it a good data model? That really depends upon the context that the model is being used, but the reality is that human beings implicitly are used to creating classes by specifying constraints. We are all natural ontologists, at a basic level.

What differentiates an ontologist typically is that they have more experience dealing with patterns of modeling than most people do, and consequently, they have developed a more comprehensive methodology for modelling that helps to identify the best way of establishing specific data structures.

In many respects, what is driving the evolution of SHACL is the realization that the older methodologiest that informed both Linked Data and OWL are too complex for most people to work with, and that by rethinking a lot of what we know about constraint modelling, it makes semantic data modelling much more open to people in other disciplines, from traditional data modelling (UML, TOGAF, etc.), programming (classes, templates), taxonomy management (library science, data curation), industry (banking, insurance, supply chain management, entertainment), accounting, medicine (HL7, SNOMED), publishing (the entire XML-based community), government, and so forth.

Yes, SHACL has its own idiosyncracies, but I’ve found with my own students that they generally understand SHACL much more quickly than they do OWL, because it aligns with the way that they think about data modelling. Combine SHACL+SPARQL, and you largely replace most of the structures that OWL provides. Add in reification and named graphs, and you are better able to think about compartmentalising information at different levels of scope and working with data not as assertions that have to be internally true to be consistent but as data that may be conditionally and contextually true. This simply isn’t part of the Linked Data mindset.

My suspicion is that ontology management will likely ultimately be derivable contextually, whether through symbolic means or as the process of some form of generative AI. This actually becomes very important, because data is very seldom static - it evolves dynamically, and even over the course of developing an ontology framework, the underlying assumptions may very well change, invalidating that model. However, an understanding of the domain and how it translates into the requirements for effective data modelling is still very useful.

Personally, I see an ontology as a contract - you and I agree that this data should have this shape at this time in order to allow for the facilitation of information, and that should the context of that information change, then we will revisit the contract. Generative AI is potentially a powerful tool for doing this, as it is fundamentally generative, but it also means that perhaps it is time for us to move beyond Linked Data as our relationship with other data evolves.

In Media Res,

Check out my LinkedIn newsletter, The Cagle Report.

If you want to shoot the breeze or have a cup of virtual coffee, I have a Calendly account at https://calendly.com/theCagleReport. I am available for consulting and full-time work as an ontologist, AI/Knowledge Graph guru, and coffee maker.

I've created a Ko-fi account for voluntary contributions, either one-time or ongoing, or you can subscribe directly to The Ontologist. If you find value in my articles, technical pieces, or general thoughts about work in the 21st century, please contribute something to keep me afloat so I can continue writing.

Never liked Linked Data from Day#1 - and your point - only Ontologists can create ontologies kills adoption and use.