Tips for Building Knowledge Graphs

Some thoughts about constructing knowledge graphs

Over the years, I’ve been involved in a few startups. True fact: most startups fail, primarily due to undercapitalisation, but also because they don't really know what they are trying to build, or because they don't understand what the market needs. Since then, I have advised others going through the startup process as well as those putting together RFP responses for research projects.

With the dawning realisation by a number of business managers and entrepreneurs that LLMs and GenAI really need some kind of a backing foundation (let’s call them knowledge bases or knowledge graphs) there has been an uptick in the number of people who basically want to know both how to build a knowledge graph and how to monetise them.

Ultimately, these both come down to a very simple question: why do you need knowledge graphs in the first place? If the answer is because some influencer somewhere (may even have been me, for that matter) said “you need knowledge graphs”, then it’s worth stepping back a little bit and understanding the WHY part of that assertion.

The Technical Value of Knowledge Graphs

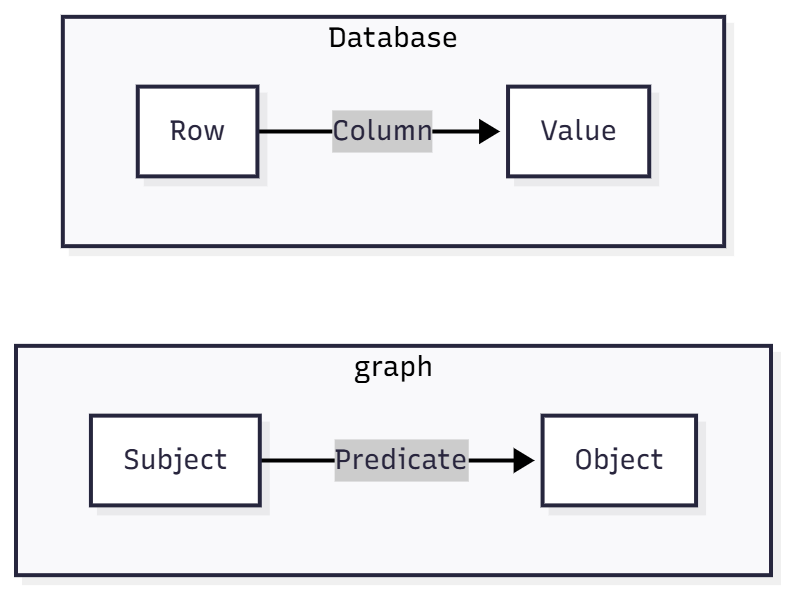

A knowledge graph is, first and foremost, a database. It is simply another way of encoding information in a retrievable format. A triple, at its core, is a way of referencing a cell in a table

Once you get this abstraction out of the way, everything else ultimately is gravy. If the value in question is a literal (a number, date or string), this is the end of the story. On the other hand, if the value is a foreign key linked to another table, the abstraction becomes a little more complex:

In database parlance, the link between a foreign key and a primary key is called a join. Such joins can give the illusion that you have several tables with large numbers of columns that repeat with each variation of the joined table. In the RDF world, on the other hand, there is no table - the object of one triple becomes the subject of another.

Put another way, there are no physical tables in graphs. With most schemas (also known as ontologies, though they aren’t quite the same thing), the closest analogy to a table is a class:

In this class, the subject is of a certain class (Class 1) while the object is of a different class (Class 2). In this particular case, Class 1 and Table 1 are analogues, as are Class 2 and Table 2. They are not the same thing, but they serve similar roles: identifying properties that are more likely to co-occur (e.g., a person class and a company class).

One of the big differences between a knowledge graph and a database is that the predicates can themselves be defined in terms of other relationships. This can be useful for capturing general schema information (typically things like cardinality and class relationships), but also can contain additional metadata such as property names, provenance information at both the data and the metadata level and additional constraints that are often difficult, if not impossible, to specify in more traditional SQL databases.

Another difference is that relational databases rely on a concept called NULL, which is required when a field does not have a value. NULL is a kludge, but it is a necessary kludge because relational databases are purely tabular in nature - if you are lacking data, you need to create an intermediate value that conceptually doesn’t make a lot of sense. In a graph database, on the other hand, you don’t have this specific requirement - if no information is available, there simply is no relationship (no triple).

RDf-star introduces a slight wrinkle to this. With RDF-Star, you have the ability to annotate an assertion (a triple) with a value that may indicate the probability (or prior) that a statement is true. This is impossible in relational databases because a column is not implicitly an entity in its own right, nor is there a way to talk about a triple as an entity.

These are structural distinctions, though they are significant: as the number of tables increases, the complexity of managing them and the inability to perform significant schema manipulation of those tables mean that knowledge graphs scale better for highly interconnected data. As a rule of thumb, this critical threshold seems to be at about thirty tables, give or take a few. Below this, a knowledge graph is likely overkill; above this, it can scale dramatically better.

The Business Value of Knowledge Graphs

In the data modelling world, there are generally classes of things and classes that connect things. A vehicle or a person, for instance, is a class with a number of properties, but for the most part, these are primarily descriptive. A contract or a role, on the other hand, is less tangible but often serves to bind two or more classes together. These latter classes often have immense value to an organisation, but classical data modelling, based solely on things, often misses them because they aren’t necessarily physical entities.

This is part of the reason why that thirty-class ceiling isn’t as high as it may seem at first glance. Once you start factoring in various taxonomy classes that are frequently sequestered by topic, you zoom past thirty classes (and even three hundred classes) very quickly. You can cut this down by talking about a generic taxonomy class, but even there, you often need to combine this with a second set of constraints that may be tied into that taxonomy (in other words, you don’t really gain much advantage IF you are dealing with a relational database).

On the other hand, such constraint management is where knowledge graphs shine. This is where inferencing comes in. If you’re running a coffee company, for instance, you may want to indicate that a given food item is a sweet baked good, a savoury wrap, a holiday special treat and so forth, and to do that, you can talk about a general category such as taxonomy types, but also indicate WHICH food item type each individual entry has.

A big advantage that knowledge graphs have is that you can define these types of relationships that can dramatically reduce the number of classes involved through generalised inferencing. This can be done via OWL (the Web Ontology Language) or SHACL (the Shapes Constraint Language), using SPARQL (a knowledge graph query and update language), and illustrates one of several ways in which having access to this metadata becomes very useful.

This also represents a significant shift in how you think about applications. A few years ago (and in many cases, this is still true), databases were where you stored intermediate products, but with the business logic tied up in code applications. This effectively meant you were dependent on your developers to determine how things related to one another, how processes were managed, and so on.

With a knowledge graph, on the other hand, it becomes possible to store a lot of this process information within the database itself. This data design-oriented approach means that different developers can access the same process information and business logic, which results in simpler code, faster development, and easier maintenance. maintenance. It also means that if conditions change (and conditions always change) these can be updated within the knowledge graph without having to rewrite a lot of code in the process. This translates into greater transparency, better reporting, more flexible applications, and improved consistency within organisations.

Knowledge Graphs and AI

The use of knowledge graphs was gaining traction in the tech sector until about 2022, when the AI hype machine began to radically distort how companies dealt with data. At first blush, large language models (LLMs) seemed like a dream come true - ingest a huge amount of documents, then you could query that data in any form you want without requiring specialised languages or programmers.

By the end of 2023, however, it was becoming obvious that there was a problem. LLMs hallucinated, creating incorrect data, sometimes wildly incorrect data, with a lack of consistency. One solution that emerged to solve this problem (until the LLMs could be improved enough to be accurate) was to feed in data from data sources such as knowledge graphs as part of the prompts, through a mechanism called Retrieval Augmented Generation, or RAG. This helped some, but because these models relied on a fixed-length buffer called a context, the signal (the knowledge graph content) eventually disappeared in the general noise of the LLM and had to be constantly refreshed.

Two years later, there’s a shift taking place in organisations. The LLMs aren’t necessarily going away, but they are increasingly being relegated to the role of being transformers for back-end symbolic data stores (knowledge graphs). That is to say, the LLMs become a natural language bridge for querying the stores, and once the results are produced, they also become a similar bridge for converting the results of such queries into natural language output:

As it turns out, this model is not really that different from how knowledge graphs were utilised previously, save that the input and output were usually less “natural-language” -y.

There are two ways to accomplish Step 2 (LLM Converts prompt to query). The first is to have the LLM write a SPARQL query that takes the requested input and queries it. This approach is powerful but often really hard to pull off in practice because it requires the LLM to have a full understanding of the graph's structural ontology (which, perforce, requires loading the ontology into the context).

The second, and usually preferable, approach is to pass a SHACL file describing the “free variables” within a given set of SPARQL queries (e.g., those variables that are often used in a VALUES statement or that form constraints) as well as a description of which queries are currently defined for the system. This sounds like more work, but in practice, it is far more common for there to be a standard application programming interface (API) that the knowledge graph exposes, with SPARQL queries on the other end of those APIs. This can be broken down as follows:

There are several advantages to this latter approach:

The LLM needs to know only as much as necessary to describe structures (the easy part), especially as schema files are comparatively compact.

There is an inherent security here - neither the LLM nor the user is actually talking to the database directly, but rather is selecting the best possible scenario for their question. This also keeps people from asking for all 100 million records at once, which will bring any database to its knees

Both the SPARQL query and the underlying schema can be changed by the programmer without affecting the broader change - if more constraint variables are needed, they can be supplied by the SDF.

This works very well for frequent queries (finding items or items based on a given class with specific constraints, for instance, or retrieving filtered lists of classes), as the SDF can both identify common patterns and indicate expectations for incoming data.

These can readily be transformed into JSON-LD (JSON with some namespace configuration files) for consumption down the road.

There are a couple of disadvantages to this approach as well:

A programmer or DBA (and ontologist in this case) will need to write both the Shacl description file and the corresponding queries.

Unanticipated queries can’t be asked.

A service endpoint will need to be stood up to handle the requests to the knowledge graph

None of these are insurmountable (indeed, they are fairly typical agentic requirements), but this also serves to highlight the fact that a good agentic service doesn’t replace human coding with cobbled together vibe coding, but rather uses the strengths of both LLMs as classifiers and transformers and the ability of programmers to build secure systems to build architectures that combine the best of both.

Building Good Knowledge Graphs

There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch, author Robert Heinlein once famously wrote. This is as true in data design as it is in most endeavours. In my experience, the hard part of building a knowledge graph is not the technical aspects, but identifying the types of things that are connected, acquiring good sources for them, and figuring out how they relate to one another.

These can be quite varied. For instance, suppose I have two lists: one of people and the other of companies. There are many potential relationships among these. For instance, a person may be an employee of a company, but also an account manager with another company in their portfolio. A person will probably also be an employee of one company and an account manager of another.

Someone, somewhere, needs to identify, encode, and load this information into the knowledge graph, or into a data source or stream that informs it. All too often, database development is lazy and depends upon forensic acquisition. What this means is that, typically, somewhere along the line, someone wrote an application that updated a database (or, more often than not, put something into a spreadsheet) that identified both the entities involved and some hint at their relationships, usually for some purpose other than building a knowledge graph.

A knowledge engineer can be thought of as the Sherlock Holmes of the data world. They typically have to take this disparate data, convert it into a compatible format, identify the salient relationships, and then upload it to a comprehensive data model before any value can be derived from that knowledge graph. In other words, human beings quite frequently have to bear the brunt of getting the data into a form that is consumable by computer systems, either at the point of data entry or at the point of data forensics.

This doesn’t mean that such an engineer can’t take two spreadsheets and work with an LLM to build a “starter” ontology that can identify obvious relationships. As a frequent “knowledge engineer”, I utilise AI quite often here because, frankly, it is a tedious task otherwise. I also employ tools such as tarql or sparql-anything, and an AI, to build these scripts (scrutinising the results VERY closely) so I can do this with data without spending any more tokens on the process than I absolutely have to. I normally store the resulting triples in separate graphs as I’m doing the forensic analysis, and when I find something that captures the relationships between two previously unrelated classes, I can add them to the knowledge graph itself.

I have made this argument before, but I will make it again here. It is better to create your own knowledge graph ontology, though possibly building on existing upper ontologies, than it is to try to shoehorn your knowledge graph into an ontology that wasn’t designed with your needs in mind. There are a number of such ontologies, including Dave McComb’s (Semantic Arts) GIST and Barry Smith’s Basic Formal Ontology (BFO), that are good for general modelling, and Schema.org’s ontology can often be a good reference point for building out your own.

However, I often use these not as primary classes but as inheritable superclasses, because a point will come when I want to build beyond what these base classes offer. Indeed, a good rule of thumb is that the moment you extend an ontology, you have also bifurcated it, in effect creating alternative pathways for defining entities. It is a different ontology.

One purpose of an ontology is to exchange information between parties (messenger ontologies). Another purpose is to store information in a way that is readily accessible and efficient (canonical ontologies). These are not always compatible with one another. Again, when designing your knowledge graph, be thinking about these as different constraints on the model, and ask whether it is possible (and efficient) to transform a canonical internal model to a messenger model and back again. If so, which target messenger formats do you want to look at?

One of the most significant developments in SHACL 1.2 is the use of computed expressions, which allow properties to be generated within a SHACL description. This makes the kind of transformations from an internal canonical schema. This may, in the future, when this technology is fully implemented, enable data-driven transformations based on a schema between the canonical and messenger formats.

Understand that the way that a given exterior source is modelled may not necessarily be optimal for anything - it was done in an ad hoc way because people were less concerned about data consistency than they were in storing information in the database in the first place (also, many times they were just badly modelled). Take the time to build and test example use cases, and incorporate them into the overall knowledge graph. Cardinality, in particular, should be tested, as it frequently determines the larger-scale data shapes.

You Still Need the Data

One last point that is worth emphasising. A knowledge graph ontology does you absolutely no good if you don’t have the data to support it. Forensic data sounds good in theory, but in practice, it is often poorly structured, of dubious provenance, dirty, poorly governed, and, in many cases, may not even exist. Data gathering is expensive, and all too often, you don’t have any control over the format that this data comes in.

One of my ventures over the years involved working in car sales, specifically used-car sales. Something that became obvious fairly quickly was that the biggest challenge was not technical, it was logistical: someone needed to gether information about what particular features and customizations a car had, needed to be able to identify model numbers of critical components such as engines and transmissions, needed to determine asking price, negotiation limits, point of contacts, needed to get photographs of the car, and all of the other things involved in the identification and sales of a vehicle. This needed to be timely and as accurate as possible. This data acquisition was far and away the most costly aspect of the whole business.

This holds true for almost all data operations. A large corporate publisher I worked with spent a lot of money and manpower trying to keep up with the status of the companies it was monitoring, something that easily dwarfed its IT costs. Most medical electronic health record systems fail not because of technology but because people underestimated the difficulty of acquiring data in the first place, particularly when that data was seen as a commodity to be bought and sold.

Before planning any knowledge graph of significant size, ask yourself whether your organisation has access to the data about the things that are of significance, how much it would take to make that data usable if you do have it, and how much it would cost to acquire the data if you don’t. Sometimes you can create proxies that serve as placeholders until you have the data (it is rare that you will have all the data you need at the same time). But the model should reflect this uncertainty as well.

Finally, and this always holds true, you should have a strategy for evolving the database over time. When a car gets sold, it should no longer be on the market until it is put up for sale again, at which point the metadata needs to be re-evaluated. This can be handled through reification, but building a mechanism into the model to account for change and the passage of time is crucial.

Don’t Count Out Micrographs

Not all knowledge graphs have billions of triples. Some have only a few thousand, small enough to be considered a micrograph. Micrographs are the Excel files of the semantic world - small, lightweight, portable, and capable of transmitting just enough information to be useful. They are small enough to be queried and updated as files rather than in a large, indexed database, even though this may not be as efficient.

While Turtle can still be used here, most micrographs will likely be in JSON-LD. Multiple systems provide tools (in JavaScript, Java, Python, and other languages) for loading micrographs as in-memory graphs, which can then be queried via SPARQL. Again, such micrographs can also contain their own SHACL for structure and validation.

Micrographs are quite useful for edge devices that need to manage just enough state that an internal JSON object might become too complex. Again, because RDF is an abstraction of a format rather than a format per se, such micrographs can also be bound to devices or digital twins. They can also serve as domain-specific languages, a topic I’ll explore in more depth soon.

Summary

As with any other project, you should think about the knowledge graph not so much in terms of its technology as of its size, complexity and use. A knowledge graph is a way to hold complex, interactive state, and can either be a snapshot of a thing's state at a given time or an evolving system in its own right. Sometimes knowledge graphs are messages, sometimes they represent the state of a company, a person, or even a highly interactive chemical system.

The key is understanding what you are trying to model, what will depend on it, how much effort and cost are involved in data acquisition, and how much time is spent on determining not only the value of a specific relationship but also the metadata associated with all relationships.

In media res,

Check out my LinkedIn newsletter, The Cagle Report.

I am also currently seeking new projects or work opportunities. If anyone is looking for a CTO or Director-level AI/Ontologist, please contact me through my Calendly:

If you want to shoot the breeze or have a cup of virtual coffee, I have a Calendly account at https://calendly.com/theCagleReport. I am available for consulting and full-time work as an ontologist, AI/Knowledge Graph guru, and coffee maker. Also, for those of you whom I have promised follow-up material, it’s coming; I’ve been dealing with health issues of late.

I’ve created a Ko-fi account for voluntary contributions, either one-time or ongoing, or you can subscribe directly to The Ontologist. If you find value in my articles, technical pieces, or general thoughts about work in the 21st century, please consider contributing something to support my work, allowing me to continue writing.

Thanks, clarifies much. Graph structurs, beyond databases, are the real power.

Thanks Kurt! I'd love an example of "a SHACL file describing the “free variables” within a given set of SPARQL queries (e.g., those variables that are often used in a VALUES statement or that form constraints) as well as a description of which queries are currently defined for the system." -- do you have a reference or examples you could provide?