Knowledge Graphs and AIs

Copyright 2025 Kurt Cagle / The Ontologist

I was asked a question recently - what’s preferable costwise for an enterprise: LLMs or knowledge graphs? This was worth digging into a bit, and while I don’t have hard numbers here, the answer really comes down to what you want to do.

Understanding the Differences Between LLMs and Knowledge Graphs

To answer this, it’s worth understanding that a large language model is not a knowledge graph in and of itself:

A knowledge graph is, at its core, a database. While there are many different kinds of databases, almost all of them work upon the idea that you present a key or identifier and get a response corresponding to that identifier. That response may be a table row, a joined data structure, a JSON or XML document, or an image or similar media resource. Still, the important thing in all cases is that what gets returned will always be the same as long as the database is unchanged. This principle is called consistency. A knowledge graph in this regard can be thought of as being indexed-based - you put in an identifier, and you get back what was stored in that index.

A language model, on the other hand, uses machine learning to identify patterns coming primarily from documents to retrieve a narrative description based on how content is used within this training data. There are no keys, only prompts, and what gets returned from those prompts is returned as a narrative that likely isn’t consistent, even if it is often descriptively correct. A language model can be identified as prompt-based - you put in a prompt (a description or set of keywords), and you get back the prompt and whatever information is most similar to the prompts as a sequential narrative.

I call a language model a confabulator because it makes up fabulae, or fable (tales) in Latin. It’s very good at this, especially since such confabulations can make complex content more understandable.

Indexed-based systems are ultimately helpful only if you have the relevant keys to retrieve the content. Ordinarily, people don’t have those keys. This is why, typically, a knowledge graph (here used very generally to mean most kinds of databases) relies upon a query to generate rows from tables that contain one or more properties with associated values, each row in turn having a referenced primary key. What differentiates databases is primarily the ability of that database to stitch together rows (and more complex structures) based upon the primary and foreign keys with each dataset, usually creating intermediate virtual tables in the process (which is what a JOIN does in SQL, is almost the entire role of SPARQL, and even, at the end of the day, handles constructs of document databases in XML and JSON).

Queries are not quite the same as prompts, though some overlap exists. A query language usually requires that you have some consistent structure that connects the items from the graph formed by foreign keys connecting to primary keys. This consistent structure needs to be known ahead of time. If you look deep enough in an LLM’s algorithms, you see something similar: empty context tokens that act as placeholders to identify potential subsequent tokens.

An LLM is a brute-force instrument - it has to do millions or even billions of these matches for every prompt, and the more complex the prompts, the more the number of such comparisons rises; what’s worse, the simplest prompts can often be the most wide-ranging. What makes LLMs so potent is, in part, that you don’t need to know the query language to retrieve content, nor do you need to directly transform the content once a corresponding sequence of output tokens is generated. You just have to be willing to pay the price for this capability:

These computations are costly, both in terms of compute power and in terms of energy expended. This cost is often more costly than using an existing query language on a given structure that’s known.

If your prompt is underspecified, you are much more likely to generate hallucinations. Yet, most people tend to underspecify their prompts because they don’t understand (or have access to) those structures.

Everything in an LLM is public. You can’t say, “this information should be hidden to those without the relevant credentials with an LLM”.

You can’t curate an LLM; you can only rebuild it from sources. This is a significant limitation.

LLMs do not have long-term persistent memory - they only have context. Once that context reaches a certain length, it loses older information.

So, what does that mean for knowledge graphs (KGs)? Once you factor in the negatives for LLMs, the principal benefits that they offer in the data space ultimately come down to two factors over existing comprehensive KG-like graph systems - LLMs are easier to query and easier to format responses to the results.

One reason that I like knowledge graphs is that - if you do have a consistent underlying pattern for structuring content, they are reasonably queryable in their rights with natural language processing, perhaps with a lighter weight kind of quasi prompt.

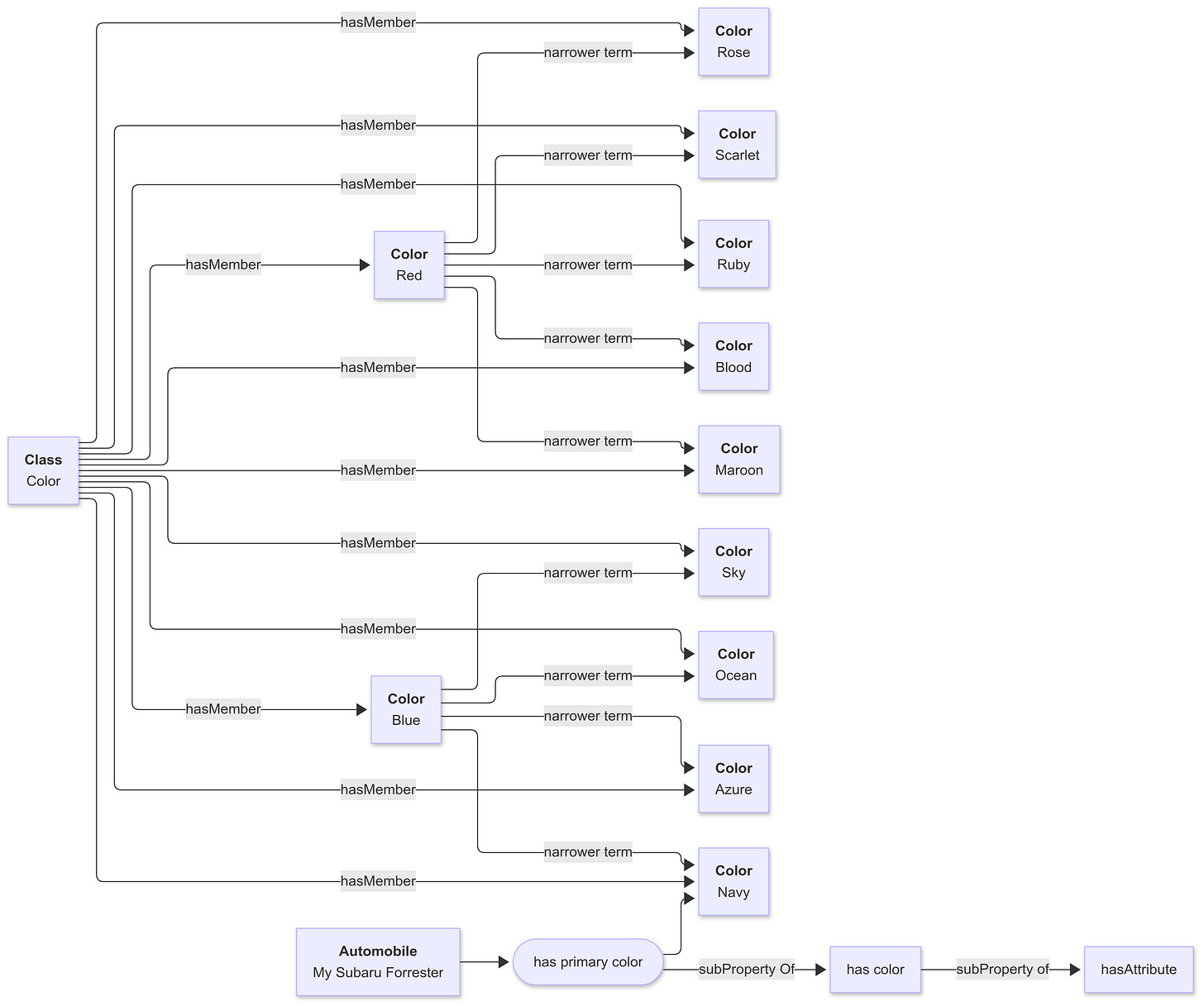

For instance, consider the following micro-knowledge graph:

Suppose that you asked, “Find all blue automobiles”.

There is a direct query that can be made:

# SPARQL

... namespaces

select ?automobile where {

values ?testColor {Color:Blue}

?automobile Automobile:hasPrimaryColor ?color.

?color Concept:narrowerTerm* ?testColor

}

}This says, assuming the test colour is blue, find the automobile that has the primary colour that is either blue or some narrow term of blue, such as navy. That is a reasonably quick query involving only three edges, but it does require knowledge about the model.

On the other hand, this can also be set up in a more generic fashion.

# SPARQL

... namespaces

describe ?thing where {

values (?testAttribute ?class) {(Color:Blue Class:Automobile)}

?thing a ?class .

?thing ?property ?attribute.

?property rdfs:subPropertyOf* Property:hasAttribute .

?attribute Concept:narrowerTerm* ?testAttribute .

}

}This is more complex on the surface, but it is also a template for any number of different kinds of objects that all have the same attribute value (or set of attributes).

These templates can the be associated with patterns determined by a natural language processing (NLP) toolkit (there are several for both Python and Javascript) that can be ranked by priority (usually depth of query), then ordered by that priority. Once a template is tried, if it returns a result set, then this is returned, otherwise a different template is applied until the list of all templates have been exhausted.

This kind of mechanism might seem more complex, but consider this - most queries realistically can be encoded in perhaps a couple of dozen different templates (and the vast majority can be handled by a handful of those).

The time necessary to run the above query is on the order of microseconds to low milliseconds for most knowledge graph systems, compared to potentially dozens of seconds on far more expensive LLM systems. If there are no blue cars in the database, then you will get a definitive answer that there are no blue cars in the database, not an attempt to tell you about their chartreuse or burgundy vehicles.

What about presentation? Again, this is a situation where you can take advantage of commonalities. One of the big reasons that I like SHACL is that it is surprisingly good not only at validation but also at providing structural information, including data groupings, ordering, and interfaces (DASH provides several basic interface identification components. This means that you can use the structural definitions of classes and properties via SHACL to have the system self-describe the instances of the class in question and then map these to various kinds of output.

Again, a relatively small amount of work upfront can get you powerful returns on the presentation side for a very small fraction of the cost of even large commercial language models. This, in turn, means that your interface is much more likely to be internally consistent (whether for web interfaces or report generation), which isn’t always (or even usually) the case with LLMs.

Finally, if you feel that you need to incorporate AI in your system (maybe you need to show earnest on your company’s AI initiatives or something equally Dilbert-esque). You can always use the knowledge graph to generate your query response and pass that response as a prompt to an LLM to have it “decorate” the content.

For instance, the following is the generated JSON output from a superhero database indicating female heroes and villains. This can be passed to an LLM:

[

{

"Name": "Batgirl",

"CharacterType": "Superhero",

"Gender": "Female",

"Publisher": "DC Extended Universe",

"DNDAlignment": "Lawful Good",

"MyersBriggsType": "INTJ",

"Appearance": "Long red hair, bat-themed costume with purple and yellow color scheme, bat symbol on chest",

"Comment": "The daughter of Gotham City Police Commissioner James Gordon, who becomes the crime-fighting heroine Batgirl, using her intellect, combat skills, and advanced technology to protect Gotham City.",

"characterType": "http://theCagleReport.com/ns/CharacterType#Superhero"

},

{

"Name": "Batwoman",

"CharacterType": "Superhero",

"Gender": "Female",

"Publisher": "DC Extended Universe",

"DNDAlignment": "Lawful Good",

"MyersBriggsType": "ISTJ",

"Appearance": "Long red hair, bat-themed costume with red and black color scheme, bat symbol on chest",

"Comment": "A wealthy heiress and cousin of Bruce Wayne who becomes the crime-fighting vigilante Batwoman, using her advanced combat skills and technology to protect Gotham City.",

"characterType": "http://theCagleReport.com/ns/CharacterType#Superhero"

},

{

"Name": "Black Canary",

"CharacterType": "Superhero",

"Gender": "Female",

"Publisher": "DC Extended Universe",

"DNDAlignment": "Neutral Good",

"MyersBriggsType": "ESTP",

"Appearance": "A blonde woman with wavy or straight hair, often wearing a black leather jacket, fishnet stockings, and a form-fitting bodysuit. She is known for her striking blue eyes and athletic physique. Her costume often includes gloves, boots, and a choker. In some versions, she also wears a domino mask. Her signature look exudes a mix of classic noir and modern street-fighter aesthetics.",

"Comment": "Black Canary is a skilled martial artist and street fighter, who possesses a powerful sonic scream known as the Canary Cry. She often fights alongside Green Arrow and is a member of the Justice League and the Birds of Prey.",

"characterType": "http://theCagleReport.com/ns/CharacterType#Superhero"

}, ...

]The key point to note here is that an LLM, in general, returns the prompt data as part of the response data, so this can often be used to not only provide summaries but also to add additional characteristics as appropriate (this is a technique I use quite frequently).

However, it also should be pointed out that there are any number of ways that you can transform data structures - JSON, XML, CSV, etc., that do not require the use of LLMs. XML offers both XSLT and XQuery, JSON can use templates built on template literals in Javascript or f-strings in Python.

AI - A Shinier Hammer

Let’s shift the discussion to technology costs, both obvious and hidden.

There are a lot of knowledge-graph-capable technologies at this point, ranging from several open-source solutions to enterprise- and government-grade systems (with price tags to match, naturally). Some of these are RDF-based, some are GraphQL, some are OpenCypher or GQL or some other variant, but all of them are predicated on using graphs to store, traverse, retrieve and transform information, usually across multiple potential formats. A growing number of these also incorporate vector stores to do similarity and clustering analysis, in effect supplying some of the same capabilities as LLMs but in a more “advisory” fashion (you can, for instance, build a very solid recommendation engine with a knowledge graph in conjunction with a vector store).

A typical knowledge graph is an evolutionary process - lay out a design (or schema), identify and semantify items for inclusion, curate, access, rinse and repeat. It provides consistent and locatable information about the resources in your organization - customers, products, resources, facilities, sources, etc., information that can be specialized for different purposes, from web content to print to powering processes and performing analytics.

It can be used to drive or ground AI, which can then be seen primarily as another medium for distribution and interaction, more conversational than traditional web applications, but at the same time far more accurate than trying to store that data in the far more uncertain domain of LLMs.

This is, of course, not the narrative you hear from the tech press, which tends to turn everything into a hammer and nail problem, with progressively shinier and more elaborate hammers. The dominant story that you hear is that LLMs - that “AI” - is both inevitable and should be all-encompassing, and so more and more effort is being made to put lipstick on pigs. Use LLMs with good quality sourced, curated knowledge graph data as a transformation, yes, but stop trying to turn them into databases.

There is a strong analogy here with Hadoop, which was a big technology from about 2009 to 2015 or so. Hadoop came into prominence as a way to perform map-reduce operations on grid computing - in essence, extending the iteration and subsequent post-processing paradigm on multiple machines at once. As an idea, it was transformative because it meant that you could do in parallel what once was a large serial (and hence slow) operation. Had it stopped there, Hadoop would have established itself as a useful programming technique.

However, perhaps because the mobile wave was finally subsiding, there was a lot of hype for the idea of Hadoop becoming the next major form of database - after all, if you have the ability to process data, then store, index and retrieve that data would seem like a natural next step. Several Hadoop-based companies were formed and money poured in from investors hoping to catch the NEXT BIG THING! An entire ecosystem evolved around Hadoop, and for a while, Hadoop and Big Data were everywhere.

There was only one problem with this scenario: Hive and Pig and the rest of the Hadoop “database” ecosystem was slow, ungainly, very processor intensive, and only worked well in specific scenarios, such as when you needed to keep data for regulatory purposes that would likely only be used in cases of depositions. Meanwhile, other companies found preferable online data storage techniques with better performance metrics, were more secure and auditable, and didn’t tie you to one vendor. At the end of the day, a lot of investors lost a lot of money with Hadoop, and, outside of a few very specialized applications, Hadoop (and Big Data) disappeared from the lexicon. This should be an object lesson for every breathless LLM evangelist - stretch a technology too far out of its comfort zone, and it will snap.

A Cost Analysis

I don’t have hard numbers here, but there are several key metrics that you should look at when comparing (or integrating) LLMs and Knowledge Graphs:

Training vs Curation Costs. KGs and LLMs involve pulling together a huge amount of raw data and extracting meaning from it. LLMs take the Hoover approach - pull in enough news sources, reports, opinions, datasets, etc., with comparatively little regard to validity or even suitability. In theory, you will reach a point where the inherent “structure” of this corpus as a model for language will emerge. KGs, on the other hand, start with a model (that can evolve) and then ingest and semantifies data into explicit connections. This requires more work upfront and as an ongoing process, but it also ensures that the data is current, can be edited as needed, and has a well-defined structure that makes it easier to use in subsequent pipelines. Suppose you can mostly automate the pipeline with human oversight. In that case, the overall cost of generating the KG will likely be much lower than that of producing a large-scale LLM, even with more labour involved.

Expertise Costs. One way of thinking about semantification is the process of refining data based on expertise. The reason that KGs enhance LLM accuracy and reduce hallucinations is that they provide context to that data that makes it more likely that what comes back from a call to an LLM was what was intended to come back, as well as to consolidate (expert) curated data with linguistic analysis. Machine Learning proponents try to make this Mixture of Experts (MoE) LLMs as well that can then be invoked from a single LLM acting as a router/consolidator, but the reality is that such expertise is often just as readily available from a knowledge graph with more reliability and consistency at a lower cost.

Transformation Costs. An LLM works by literally creating a narrative - in essence, constructing sentences in order one word (or token) at a time. That’s powerful, but it is also computationally expensive, especially if it’s doing reasoning work as well. This is part of the reason for the prevalence of chat interfaces - it’s the best way of handling conversations that may take upwards of a minute or more to compute. With a KG, you can create algorithmic transformers that are far faster because they aren’t trying to compute conversational content but are simply substituting items in templates. What’s more, they require orders of magnitude less compute and don’t force systems to keep a connection open (and hence require more servers) for long durations of time. This translates to lower bandwidth costs as well.

Liability Costs. You, as a company manager, do not want to say, “What you are reading may be a lie.” Raw LLMs, especially with poor prompts, can make things up that commit your organization to specific actions inadvertently that may be considered offensive, that may be sensitive, such as HIIPA data, or that may provide inaccurate information that could then be used for claims of damages. With a KG, you ultimately control your message - what goes out is precisely what you want to go out.

Technical Debt. Code generation, one of the big use cases, makes some sense when it is part of a process with a human in the loop. However, that code is still buggy and suboptimal and likely will be for some time. When AIs are used autonomously for immediate code generation, there is no consistency because there is insufficient context for the LLM to understand how best to both integrate that code into the larger architecture and to do so in a way that can be readily maintained. On the other hand, you can build complex transformers as one-offs via LLM that can work consistently with KGs, again assuming a human in the middle. This reduces the costs of technical debt maintenance, which can often significantly limit the value of a project in the first place.

Labour Costs. KGs require marginally more labour than LLMs, primarily from an editorial perspective and coding perspective, but not that much more, and you are, in effect, replacing consistent coding with inconsistent prompt engineering and potential editorial rework of content that’s at 80% but needs more tweaks to account for accuracy, reliability, and intent.

The net effect of this is simple. There are areas where LLMs are great - as code assistants, a place to bounce ideas off of, and a mechanism for generating summaries, graphics, and reports. Still, in almost all cases, these LLMs work in conjunction with human beings, and even then, this also increases editorial and curational time, guaranteeing that what the LLM produces is correct.

Once you move outside of these relatively limited cases, the value propositions for LLMs become considerably poorer when taken from a total cost of ownership perspective, especially when compared to knowledge graphs, primarily due to a lack of consistency and reliability. Yes, costs per token for computation have been falling rapidly, but at the same time, the number of tokens necessary to provide more accurate or valuable responses has been rising at a near-proportional level, meaning that the total cost per computation, has likely dropped much less significantly.

At the same time, adding more LLMs as MoEs will not solve the consistency or accuracy problems significantly - it only increases the opportunity for such errors to creep in while again adding tokenization costs. Companies would do better to spend time actually curating what’s valuable to them, rather than simply using press releases as AI model fodder.

Final Thoughts

We need to get out of the mindset that we are in the “AI Age”. That’s marketing crap. We’ve been in the AI age since the 1960s, which was ironically about the time that the seeds were planted for both neural networks and knowledge graphs. Neural networks have their place - they are very good at automated classification (that’s what they were built for) and yes, there are things that you can do with transformers, with confabulators, that are jaw dropping. They are not going away.

However, at the same time they are not the perfect (or even all that good) a vehicle for either computation or data storage. Knowledge Graphs are, for a number of reasons, better for encapsulating known data, for curation, for governance, for security. They represent knowledge, in that they usually contain within them not only the fundamentals of structural data but also the relationships to entities across a potentially broad spectrum of types. In many ways they are the antithesis of the “Shoot ‘em all and let god sort them out” mentality that seems to pervade so much of what we call “artificial” intelligence.

In your analysis of data projects, ask yourself first whether you really need LLMs. You may not, and going down that pathway could lock you into a solution you really can’t easily extricate yourself from. If you do need LLMs, then look upon knowledge graphs not as a competitive technology, but a complementary one, a means of ensuring that the content that you are working with is of good quality, provenance, and description, and that the relationships contained with the knowledge graph are the ones that are most important to your organization, not just derived from subtle (and often misleading) shredded documents.

There may eventually be neuralsymbolic AI, but my suspicion is that the very things that make linguistic neural AI transformers work in the first place is that they are closer to the way that humans “think” than knowledge graphs. This is intriguing from a cognitive scientific standpoint, but databases and knowledge graphs emerged because, sometimes, we just need to have the facts, and humans aren’t terribly good at knowing those facts either. Use the tools that do the job you need, not satisfy some influencer’s marketing directives.

In Media Res,

Check out my LinkedIn newsletter, The Cagle Report.

If you want to shoot the breeze or have a cup of virtual coffee, I have a Calendly account at https://calendly.com/theCagleReport. I am available for consulting and full-time work as an ontologist, AI/Knowledge Graph guru, and coffee maker.

I've created a Ko-fi account for voluntary contributions, either one-time or ongoing, or you can subscribe directly to The Ontologist. If you find value in my articles, technical pieces, or general thoughts about work in the 21st century, please contribute something to keep me afloat so I can continue writing.